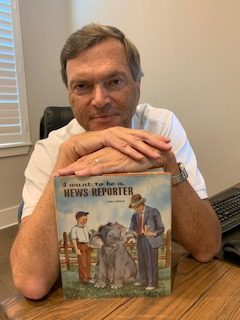

Tom Marquardt holds the children’s book that inspired his newspaper career

Careers often start with books, whether it be politics, medicine, or something equally inspirational. My career started between the pages too. During a weekly trip to a Dearborn, MI, library, I was drawn to a series of books from Children’s Press titled “I Want to Be.” I could have pulled from the shelf “I Want to Be” a dairy farmer, storekeeper, orange grower, or bus driver, and perhaps my life would have taken a different turn. Instead, I took home “I Want to Be a News Reporter.”

The story was about a boy named Don who joined his Uncle Jack, a reporter for The City News, on his way to cover the birth of a baby elephant at the zoo. On the way they came across a fire, and Uncle Jack stopped to ask questions. For a kid so shy he hid from adults, the image of me asking questions amused my mother, but at age 8 I was hooked.

By the time I was 13, I was publishing a newspaper on a manual typewriter in my bedroom. My press was carbon paper, and eventually I recruited an artist and two fellow provocateurs who met clandestinely in my house as the Writers Association. While the teachers were initially amused, the scandal sheet reached the principal, who shut down my little enterprise when I accused a schoolmate of spreading rumors. I had witnesses quoted on the record, but perhaps the headline, “Ron Scott should button up” was too much for Ron. I apologized to him a few years ago.

From that experience came a lesson that would endure: never fear the truth.

I went on to become editor of my high school newspaper and later editor of my college newspaper at Central Michigan University. I was there during the height of the Vietnam war when campuses were teeming with activists and National Guard. I had moved on from adolescent rumor-mongers to a college president who suppressed campus protests, but the reaction from authorities was much the same.

The Board of Publications, which appointed me, was displeased with my unflinching, albeit shrill editorials. It voted to censure me, the first and only CMU editor to be disciplined. Not deterred in the slightest, I drove a student campaign to separate the campus newspaper from the university and then became its first editor to guide an unbridled newspaper independent of university control. The president was happy to see me graduate, but decades later I had the last laugh when I returned to be inducted into the school’s Journalism Hall of Fame.

It was a turbulent time to be a journalism student, but the experience prepared me well for the real battles that would ensue, first at a small Michigan daily a few miles from my old campus. Two years later I was editor of the Ypsilanti Press in southwest Michigan where we broke a story on a nurse who was euthanizing terminal patients at the Veteran’s Hospital — a tip that came from a funeral director who joked to an obituary writer that patients there were “dropping like flies.” Hospital attorneys threatened to sue us if we published, but I remembered to never fear the truth no matter how ugly or consequential. No lawsuits followed when the police arrested the nurse. Our role and my contentious meeting with the hospital administrator was chronicled in a book about the crimes.

When I reached Annapolis, MD, as managing editor in 1977, I was no less defiant. My reporters covered a corrupt mayor, a corrupt county executive, and a corrupt governor, all of whom eventually served time in jail. Encouraged by a fearless publisher and a hard-charging executive editor, I embraced editorial writing. Frustrated by county bodies who dodged us by meeting in private, I led a successful state-wide campaign to overhaul Maryland’s Open Meetings Law. The effort led to a National First Amendment Award from the Society of Professional Journalists.

When the Naval Academy pleaded with me not to publish a damning expose about sexual harassment at the military school, I went back to my core lessons: never fear the truth. The story, highlighted by a tearful confession of a woman midshipman who was traumatically handcuffed to a men’s urinal, went national. We were one of three finalists for a Pulitzer Prize in investigative journalism that year.

I went on to become Capital Gazette’s executive editor and in 2012 retired as its only editor and publisher. After retirement I did one more story that had eluded me on the job: exposing a local hospital as a former Negro Hospital that practiced brain surgery on abandoned patients in the 1940s and 1950s. Countless hours of research exposed a dirty story few people knew — or were too ashamed to tell. It was one of my most satisfying stories to write and oddly one of my last.

Careers are composed of milestones, none of which can be foreseen but all of which can be enjoyed when you have a chance to look back as I am doing here. I fear the demise of newspapers will rob young journalists of this life-long opportunity, but I hope their vision is driven by the same optimism and passion.

I had forgotten about the book that gave me my inspiration so long ago until I attended a retreat for the county library foundation just before my retirement. The warm-up question for board members was how did we choose our careers. I told of the library book for the first time. The next day a curious library administrator called and said he found “I Want to Be a News Reporter” on eBay. I was the only bidder. Today the thin book stands on a bookshelf behind my computer where I am reminded that what inspired a fictional Don and his Uncle Jack was my defining moment in a long and satisfying career.

(Editor’s Note: Defining Moments is a series in SCOOP to give you, our press club members, a forum for writing about highlights from your career. Please share your Defining Moments story for an upcoming edition of SCOOP by emailing your article of 400 to 750 words to info@pressclubswfl.org, attention SCOOP Editor Karla Wheeler.)